25

May

I rarely buy postcards. I create them instead.

During my travels, I enjoy reading local newspapers, magazines, pamphlets … anything printed, really. This way I get to discover interesting aspects of the culture I am in.

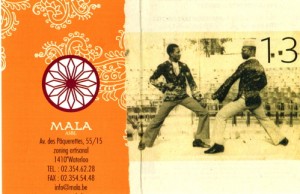

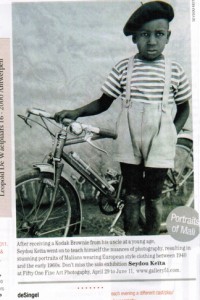

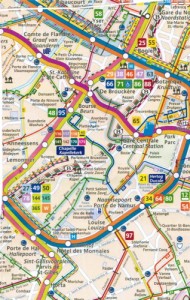

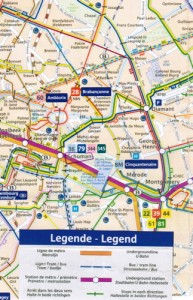

Then I make collages of the most appealing bits. The postcards are snippets of my travel memories: a map of the métro in Bruxelles, a local exhibit going on in the city or just something that attracted my attention.

In Bruxelles, I went to a cool store called Mala India, took the métro everywhere, enjoyed listening to the Flemish language, and wished I had time to hop over to Antwerp and go see Seydou Keita Photography.

So here are my homemade postcards.

If I thought my family was the only unusual one on the planet, I was wrong. Other family stories beat us hands down in African genealogy adventures.

My friend Myriam, who is Parisian of Moroccan origin, told me that in order for her mother to know her own birthday, she had to go to a cemetery in Morocco.

The tradition there was to tell people: “You were born 2 days after this person passed away. Or 7 days before so and so died.” So to know your birthdate required visiting tombstones to substract or add days to another person’s death date.

In this rare case, to be Congolese is easier. All I have to do is go to the patriarch of my family and get all the birthdays.

“What is grand-father’s date of birth?”

“I don’t know. He was pagan.”

Well, almost all the birth dates. The ones that are missing are those of my ancestors who were pagans.

Dates were not important in our Luba traditions, only events and the order of births. Later on, Catholic missionaries began to keep track of birth records.

So if you were Christian, you knew your birthday.

23

May

Bruxelles _ My niece Ngoya is coming to pick me up. I had not seen her in 5 years. She lives in Kinshasa and we are both in Belgium at the same time for a few days. When she arrives, we sit down over ice cream and chat. A Belgian friend of mine joins us.

He must have been smitten by my niece, because right away he starts to talk about how beautiful she is. Soon the word marriage pops out of his mouth. I look at him in shock. My niece pretty much ignores him, as she texts on her Blackberry.

Luba Dating: Taboo #1.

Don’t talk about marriage the very first second you meet a girl. And even if you are kidding, you do not joke about such things. His behavior was inappropriate, especially among the Baluba.

The following day, since my Belgian friend is a nice guy, I decide to tell him gently the faux pas he had committed.

“Dude! You were hitting on a girl in front of her mother. You don’t do that.”

As he looks at me puzzled, I continue. For Luba people, there is no concept of niece or aunt. These words do not even exist in the Tshiluba language. My niece is actually my daughter and I am her mother.

“In conclusion, you were wooing my daughter right in front of my eyes! AND without my permission!”

“Oh, so it would have been o.k. if you, the mother, had given me permission to date your daughter?” He asks.

“Even with my permission, you can’t slobber over a girl in front of her mother. It’s so vulgar. Besides, that will only make the girl run away from you.” No Luba woman would want a man who behaves like that.

(…unless of course, the woman was after his citizenship. But here, my Belgian friend is out of luck; my daughter-niece already has her Belgian citizenship. So no interest there).

“O.k.” my friend says “I’ll marry her and make it all proper.” He turns to a man who walks in the reception area and introduces me as his my mother-in-law.

Luba Dating: Taboo #2. You do not have permission (nor the honor) of calling anyone, your mother-in-law when you haven’t even paid the dowry.

Bye!

Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu wa Za Banga, President of Zaire

Here is a real dialogue (for the sake of privacy, names have been changed).

“What’s your husband’s name?” I ask my cousin A.

“Mobutu” she replies.

“Mobutu? I thought his name was Mutombo,” exclaims my cousin’s sister who has been sitting with us.

“Well, his real name is Mutombo, but his name in Germany is Mobutu.” Cousin A explains.

Confused? You’re not the only one. Here is what I think I understand.

Many Africans are determined to go abroad to the West in search of a better life _ by any means necessary; this includes traveling with someone else’s passport sometimes. I don’t know exactly what is my Cousin A’s husband’s immigration status, but I’m thinking new name, new country, new life.

Now try to keep track of all that in genealogy! They don’t even have such categories in genealogy softwares.

Bruxelles _

I am in the European Union capital for a few days. My business meeting is over and first things first, I need to find a shul (synagogue in Yiddish) for Shabbat service. There is a Conservative shul I found online, but it’s clear across town and I don’t feel like schlepping all the way there.

It’s Friday afternoon, Shabbat is starting in a few hours and I’m desperate. A friend suggests that I simply go out and ask any Jewish person that passes by. Dressed in my Congolese business outfit, I do just that. I am in luck. I see a man wearing a kippah and speaking in English to his son who has little curls on the sides of his face. Orthodox Jews! Perfect.

I approach him and ask if there is a shul in the neighborhood. He looks at me warily and sends me two doors down. When I knock at the door, a young woman answers.

“Do you know of any shul in the neighborhood?” I ask her.

She looks at me with suspicion and gives me an email address to find shuls in Belgium.

“Lady! It’s less than an hour before Shabbat,” I say. “Do you think anyone will read their emails before Shabbat?”

She realizes then that maybe this black woman standing before her is Jewish. So she gives me an address: “109 …”

I decide to go and check it out just in case it’s a phony address. When I get to the place, it looks like a house. There is no sign. No name. Just the number 109. A man who looks like a bouncer intercepts me even before I knock at the door.

“Is this a shul?” I ask him.

“What is your business here?” He demands.

“I want to attend Shabbat service tomorrow morning.”

“Why?”

“What’s the matter? Don’t I look Jewish to you?” I ask him, pointing to myself.

He looks at my African outfit and shrugs. I realize he’s simply doing his job; I tell him yes, I am Jewish _ from Chicago.

“From Chicago?” He asks me to wait. An orthodox man, wearing a black hat, comes out and introduces himself as being from Brooklyn, New York. “Which shul do you go to in Chicago?”

I tell him and answer all his other questions. He invites me to the Shabbat service; I must have passed the test.

The next morning, I walk to shul and find a lovely community of people from all over the world: France, Finland, Belgium, Germany, England, Slovakia… And the man from New York is the rabbi. A cute little girl comes up to me and asks why I am brown. I smile and tell her it’s because I like to hang out in the sun (my ancestors too for that matter). Praying together, there are Ultra Orthodox, Modern Orthodox, and Jews who can barely read Hebrew. As a Conservative Jew, I fit perfectly in the middle.

The people I saw yesterday, all come up to me and apologize for being so guarded. There had been some attacks on synagogues in the city. That’s why the shul looks like a house.

I am invited to the Kiddush afterwards. We sit outside in the backyard, with children, running all over the lawn. We eat and talk for hours; it feels like an afternoon spent with family and friends.

I look forward to praying in that community again the next time I am in Bruxelles, whether or not I am wearing a Congolese outfit.

20

May

In Paris, my day begins with a baguette. Yes, I eat an entire baguette. I’m hungry!

Lunch varies, depending on whether I am traveling on the metro, sightseeing or just furiously writing in the sun; it could just be a bar of chocolate.

The evening meal is typically Congolese: smoked fish slowly cooked outside on a grill, Pondu (or Kaleji in Tshiluba), which is basically cassava leaves cooked in tomato sauce, roasted caterpillars, etc. The meal would not be complete, however, without fufu.

What is fufu? you ask.

It is hot dough, made with hot water and a variety of flour. In Paris, my cousin Mbuyi makes fufu with semolina flour. Other people make fufu with cassava flour, plantain flour or even potato flour.

Fufu is your carb, your starch. It is the base of the meal; the vegetables and the meat or fish are there to accompany fufu (not the other way around).

If you ask any Luba elders, including my Dad who lives in Montreal… “have you eaten?”

They will tell you, “Today I have not eaten,” if they did not eat fufu that day.

Yours truly here must admit that, although fufu is an acquired taste, you sure can get hooked on it. Fufu is life.

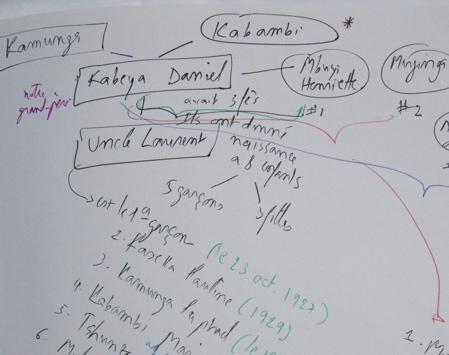

I have started creating my family tree using the Ancestry app for iPad. This has facilitated my work tremendously as I travel and interview family members from one country to the next.

The iPad is gold. I am able to travel light. No need for a laptop. And I can even forgo bringing my heavy paper notebook if I desire. I can do everything with just my iPad.

Using the Ancestry app on my iPad, I have been able to add on information directly onto my family tree during an interview.

Sometimes, such as during my recent trip to Bruxelles, my cousins did the data entry themselves. This allowed me to sit back and socialize while the genealogy work was getting done. After all I was reuniting with this side of the family for the first time in 24 years. That was a blessing.

I like the fact that the genealogy application on my iPad is linked to the Ancestry website whenever I have connection to the internet. This means the family tree gets updated online; and so I can easily share it with all my family members instantly.

Here is what I don’t like (nothing can be perfect):

1. I need to have wifi connection to edit the family tree. Without internet, my family tree can just be a show-off piece like a mere hard copy book. I don’t think the Ancestry app will work too well in the Congo. Most houses do not have wifi connection. So how am I going to use the app and continue building my family tree as I travel from village to village? I wish there was a way to edit one’s family tree on the iPad without wifi. If anyone knows how, please let me know.

2. The second item I don’t like is that I need to enter manually every single person. What if I find entire other family trees that can be linked to my own? We’re talking about large African families. I don’t want to have to copy large family trees manually. There must be an easier way. Any thought on that? Your comments will be very much appreciated.

“The practice of genealogy does not require any diploma and so anyone can do it. It only requires patience, discipline and method.”

That’s what I read in a French booklet on Genealogy.

I’m sure the people who wrote this were only talking Western genealogy. In doing my family tree, I realized that maybe there ought to be an African genealogy certificate. Such genealogy requires superpower patience, which I don’t have much in reserve. A good example is the case of “Multiple Wives.”

A Polygamous family (from http://emeagwali.com)

My people are called Baluba. We are the Luba people. Muluba is what I am; mu- is singular, ba- plural. We are known to be proud, hard working, confident, stubborn and very much disliked by the Belgian colonizers who could not quite control us.

But when it comes to genealogy, the most important characteristic of the Baluba is that Baluba men are polygamous; they love to have several wives and even more children. I have a cousin-in-law, whose father has 45 wives (not children, wives! I haven’t started adding them to our family tree yet. I hope the software won’t crash).

We are proud of our large families, except when it comes to creating a genealogy tree.

“Our grand-father had 12 children. He was a strong Muluba,” the interviewee says with pride and laughter. Our grand-father had three different wives. I quickly jot down the kids who belong to which wife. Later on, as I enter the information on my iPad, a cousin sits down next to me and says I shouldn’t enter the name of the different wives.

“Why not?” I ask, surprised.

“Because that will separate the family,” my cousin replies.

“Separate the family?!”

Here is the issue, she explains. Our grand-mother was the first wife and so the most important one and maybe her children as a result have more “social family status.” By listing the children of the two other wives separately seems, in my cousin’s opinion, to divide the children in three factions.

But then what would be the point of doing a family tree? Since men boast of having several wives, it’s public knowledge. Everyone knows it; my writing it down won’t make any difference.

Now to avoid hurting anyone’s feeling (such as writing down their real mother’s name), I am supposed to go and ask permission to every second wife’s kid, third wife’s kid, and so on, to write their mother’s name down in the family tree.

That’s insane!

If people in the family are ashamed of their mother, they should declare themselves orphan or something. I am not going to write down a fake mother’s name instead.

16

May

In Paris, I have been hanging out with pastors. Both of my cousins are pastors; They’re actually cool. We spend hours together talking about the Torah; It’s the only part of the bible we have in common (me being Jewish, them being Protestants). We diverge widely when it comes to the Jesus question, but we’re still family.

However outside of family, Jesus becomes a sore point. I went with my cousin Kabeya to visit one of his friends and colleagues, a pastor friend. As we sat down for tea in the pastor’s house in a banlieue of Paris, my cousin announced that I was Jewish. Right away, I knew my being Jewish was not going to be good news; since earlier, the pastor friend had berated non-observant Christians, saying they were the cause of hell on earth.

The energy in the room shifted. I suddenly became the representative Jew and was asked every single question about Judaism.

“What do you Jews think of Abraham?”

I kept telling him to go and ask a rabbi; after all I could not speak for the entire Jewish population. As I dragged myself through the insufferable conversation, the inevitable question about Jesus was asked.

“So for you, Jesus was just a prophet …?”

“Not even,” I replied bluntly. By then I was simply fed up. “He was just another Jewish guy who happened to be very learned.”

That did not sit well with the audience. Yes, the pastor’s wife was also present by now; she was as fervent as her husband. My cousin, he remained quiet.

Eternal Life

Then the pastor said, “Let me ask you something…” He paused and continued slowly, “Do you have eternal life?”

I froze. His question brought me back in time.

I was bicycling across the midwest. It was summer time. I stopped by a church in a very small town and asked to pitch my tent in the backyard. When I saw the pastor, my jaw dropped. The pastor was, I kid you not, the most beautiful man I have ever seen in my life. He generously offered me the church lawn as well as a huge basket of fruits and vegetables. Not only was he handsome, but kind too. I could have married him on the spot.

But then, the gorgeous pastor asked me, “Are you saved?”

All my romantic dreams came crashing down. Any lust I had towards the man disappeared.

Here I am in France more than a decade later, facing the same type of question.

“Do you have eternal life?” I don’t even know what that means! But if it has something to do with Jesus, I don’t want it. I am very happy being Jewish.