19

Jul

KASALA (Plural: Tusala) is a heroic Luba chant.

It can be a long poem that lists the names of people, lineage, clans, tribes, rivers, etc.

Kasala praises a person, dead or alive, famous or not (such as your next door neighbor). It can recount the glory of ancestral lineage, the battles of one’s clan against others, the conquests, the courage of a group of people, or simply remind listeners of their ancestors.

Kasala is a genre in traditionnel oral art. Without oral art, there is a danger for ancestral values to be lost and forgotten.

In this video, a Luba elder, Papa Kanyinda Bululu Etienne Marcel gives us a taste of kasala.

Watch VIDEO of the introduction

I asked an 88-year-old Luba elder to introduce himself.

He started by saying …

“My name is Kanyinda Bululu Etienne Marcel.”

Then he proceeded to cite all his ancestors, all the way back to the 17th century.

I have never seen a presentation more thorough.

21

Jun

In France, I discovered that the process of naming a child can be a cultural adventure.

Claudine Brillant and her husband live in a small village outside of Chartres. They decided to find a name for their child by pulling out a calendar. French calendars list names of Catholic saints and their commemorative dates.

Starting with the month of January, Claudine ran her finger down the days, looking for a name. She got to Sainte Sandrine; she looked at her husband, who shook his head. With a name like Sandrine, kids at school might tease her and call her Sardine. They finally settled on the name Sophie from Sainte Sophie found on May 25.

In Tours, central France, a young couple went cruising through old cemeteries to look for not-so-common names for their unborn child. They had a baby a few weeks ago and named her, Adelaïde.

In my family we don’t bother being creative with our name search; we honor an ancestor by naming the child after him. It keeps things simple.

“There is a mistake here. My Mom is not that old!” exclaimed my nephew, who is browsing through our family tree on my iPad.

I looked over his shoulder and checked to see.

“That’s not your Mom; it’s your great-aunt,” I replied.

The two women have the same name, Mulanga, but were born 20 years apart. Mind you, these are first names. Family names do not exist traditionally in Luba culture.

In my family, name repetition is rampant. My grandmother Mbuyi already has 7 descendants named after her; I have so many cousins named Mbuyi, including my oldest sister.

But you don’t have to follow the Luba tradition to find a name for a child. If you open old literature books, you might find interesting names like the Gaulish name, Wouivre, which means snake or a river that snakes through the landscape.

19

Jun

The meaning of spitting among the Luba people of Congo.

31

May

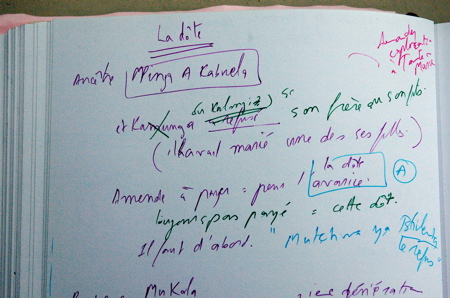

Five hours! Five hours I spent with my uncle Tshimanga, learning about one thing and one thing only: the dowry.

“It’s the cement!” My uncle repeated. “The cement that binds all the members of the family together. With the dowry system, everyone in the family gets a chance to marry. And so the family continues to grow and is strengthened.”

The dowry _ “la dote” in French _ is the base of an informal barter system created within our family. This swapping strategy acknowledges that everyone in the family has the right to get married no matter what their economic status is.

My uncle used to have the family dowry book. He lost it in his move to France more than a decade ago. Fortunately, he knows all the dowries by heart: the ones given by our family and the ones received.

I imagine the family book was written like an accounting book, keeping track of all dowry transactions. The book must have been filled with the “who’s who” of all our family marriages.

Following all this was very important, you see, since the person who helps you marry is in fact the one who shells out the dowry money for you to be able to get married. It’s like giving out a bank loan.

Since the Luba society is patriarchal, it is the men who marry the women; so they are the ones who pay the dowry to the women’s families.

My father, for example, helped his younger brother (Uncle O) get married: He paid for his dowry. Thanks to my Dad, my uncle O was able to start his own family and have children. A few years ago, Uncle O’s oldest daughter got married (her husband paid a dowry for her). That dowry was used to reimburse my Dad.

I imagine, the family ledger of these dowry transactions to look like this:

DOWRY BOOK:

Papa —> pays —> : Uncle O. marries (in 1975)

: Dowry = 1,200 FC (Congolese francs) [Out flow of cash]

Uncle O’s daughter gets married (in 2000)

<— : Dowry received = $500 (US dollars) [In flow of cash]

Papa gets reimbursed receiving $500.

I don’t know what 1,200 FC would amount to, but remember the amount of each dowry does not matter. What counts is one dowry reimbursing the other.

My paternal grand-father was the mastermind behind this dowry system. He wanted to make sure that after he passed away, his older sons will be able to help his younger ones get married. The dowry organization he created goes in even greater details, planning for all possibilities.

Even if the older sons do not have enough money to help out, it’s the dowry of their second daughters that will be used to help their younger siblings get married. Once again, I am using my Dad as an example.

Papa’s second daughter (my sister) got married. He received her dowry, turned around and used it to help his younger brother (Uncle M.) get married.

And so in the far, far future when my niece, who is about 5 years old now, gets married, my Dad will get reimbursed. Her future dowry will pay back the dowry debt that helped her father get married and bring her to the world.

Dowry debts are never forgotten!

If a dowry is not reimbursed within the lifetime of a donor, his brothers _ representing him _ will get compensated. If none of his siblings are alive, then his descendants will get reimbursed.

There is such a dowry debt in my family that has lasted for 5 generations. It is finally about to be paid.