10

Jun

Shavuot is when we celebrate the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai. I looked forward to celebrating it in Paris the traditional way: staying up all night to learn Torah.

In my Conservative synagogue in Paris, the overnight study began at 8:15 pm. The theme of the discussion was “Does G-d have a body?”

I wondered how this topic would last all night since it seemed to me an open and shut case: Jews are very much against idolatry, so we avoid any corporal representation of G-d.

Speakers were scheduled to examine the various representation and descriptions of G-d in not only Jewish texts, but also historic and literary ones.

The first speaker was a historian of ideas, Mireille Hadas Lebel. She took us through books rarely read among Jews, to see how G-d was described in texts of different time periods. She read excerpts from the book of Daniel (of the 6th Century), which is included in the Writings and not in the books of Prophets. She also read the book of Enoch, a Jewish text no longer used in Judaism, but still very much central to the Ethiopian Orthodox Christians.

And then, to the surprise of the audience, the historian pulled out the New Testament:

“If you want to know Judaism in the 1st Century, read the New Testament,” she explained.

Through all the texts Mrs. Lebel read, we clearly saw a tendency to ascribe a human form to G-d:

_ Giving Him a voice:

“ Adam answered (after having disobeyed), “I heard You in the garden, and I was afraid because I was naked; so I hid.” Genesis 3:10

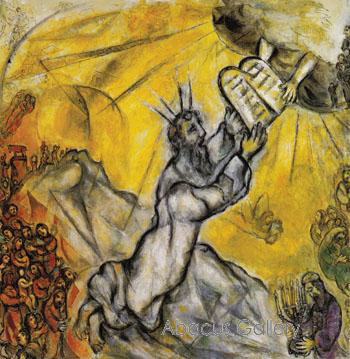

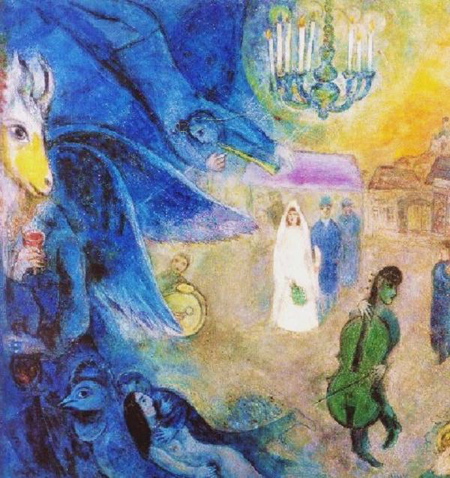

_ Using a hand or even angels with wings to represent G-d, as was often seen in the works of the Jewish painter, Marc Chagall.

The French Writer and Philosopher Voltaire was right when he said, “If triangles made a god, they would give him three sides.”

At coffee break at 9:45 p.m., we all crowded around the hot drinks and cakes and cookies. The night was young and we needed to take in as much energy as possible.

In the next talks, more discussions of G-d’s representation in Jewish and Israeli art seemed to reinforce these anthropomorphic paintings of HaShem.

Was the hand in Chagall’s painting representing a tiny piece of the unlimitedness of the Divine Being or was it limiting Him into a human form?

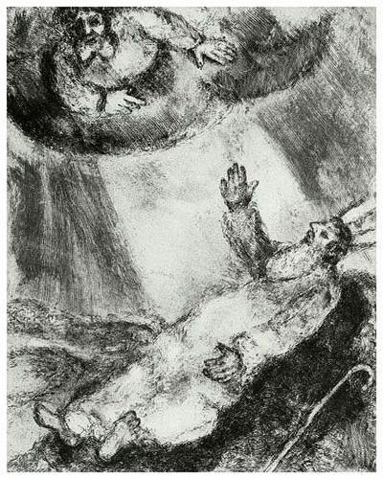

People who were present at the foot of Mount Sinai were lucky: they did not have to wonder about G-d’s form. True, they did not see Him, but they certainly felt Him that day through the thick clouds surrounding the mount to shield them.

“But,” He said. “You cannot see My face, for no one may see Me and live.”

Exodus 33:20

One person did see G-d: Moses.

He was the only one who penetrated the clouds and saw HaShem. Maybe that is why, in his painting of the dying Moses, Chagall paints G-d in a human form.

Once again, Voltaire.

“If G-d created us in his own image, we have more than reciprocated,” the writer said.

The study group continued to explore the shape of G-d late into the night. The second coffee break at 11:30pm was not as effective. My eye lids were getting heavier and heavier past midnight.

The last speaker was Rabbi Rivon Krygier. He said if there was one thing and one thing only we should remember from the whole evening of learning was to read Benjamin D. Sommer’s book, “The Bodies of G-d and the World of Ancient Israel.”

Our rabbi was truly a good speaker, engaging us into the discussion.

“Wake up!” He suddenly shouted, waking me up with a jolt. I sure hope I was not the only one in the audience, fading away.

I vaguely remembered him saying that if we wanted to know what G-d felt and looked like on top of Mount Sinai, we simply had to google “volcan de Chili.”

The clouds shielding G-d from the people below must have looked like this volcano eruption.

By 1:30 a.m., my brother came to pick me up. I stumbled out of the synagogue, as the rabbi rightly said, that I was on my way to sink into my own clouds.

7

Jun

Expect more stories of my French travels towards the end of the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, on Friday.

Chag Sameach and Happy Holiday!

Kabuika

“I came here when I was 19,” Leslie Xuereb Amiel said. “I thought I would be here for a couple of months and now I’m here for 30 years.”

Leslie is from New York City. She came to Paris to study art and art history for a few months. She fell in love with a viola player, traveled with him, stayed, painted and ended up moving to Chartres, France. Since she is American, a friend took me to see Leslie in her studio.

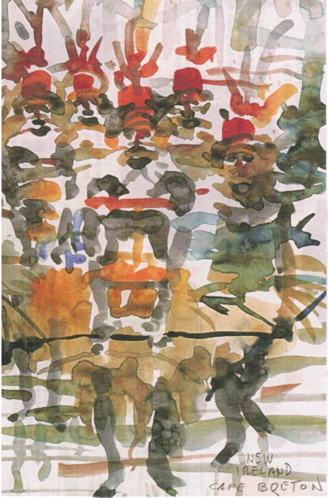

Everywhere I looked, I saw bright colors. Her studio was cool and colorful, a sharp contrast from the intense sun outside.

“I create this imaginary world as a kind of a refuge for myself, because I’m not very happy with the world [outside] as it is,” Leslie said. “[My art] has helped me run away from the real world.”

The art studio is certainly a haven. It feels good to be in it. Leslie has painted stain glass on her windows to create that feeling. The stain glass protects from the outside world and at the same time makes the studio very lively. She hopes that her happy art brightens others too, ”If I can give a bit of energy to others, that will be great.”

Leslie has been painting women with flowers as big as the women. Her art portrays “the joy of simple things, of flowers, of the sun, of the earth … the interactions between [them].”

Her paintings show women bouncing up to be part of the trees, the moon, and the air.

“All your characters are women,” I pointed out to her.

“Yeah, mostly. There are some angels here and there.” She replied. “Every now and then there is a guy; he’s more like an accessory,” she burst out laughing. “It says a lot about me.”

Leslie now has 3 children and her whole life is in Europe.

“How could you possibly imagine that when you go abroad to study, you’re going to stay for your life?” exclaimed the artist, who has been in France for almost 30 years. “I think when you make a decision, you absolutely don’t know where it will lead to.”

Her decision to come to France led Leslie to a life centered around her art.

“I don’t own a house… I rent an apartment, but I am buying a studio, [because] I need to own a place to create in.”

“It’s kind of a bit backward,” she added with a shrug. “Besides the children, everything personal goes into my brushes and paints. I don’t own jewelries. This is it!” She said spreading her hands out to show her studio.

From her life in France, Leslie realized the most important thing is ” to keep on the path of creation all the way, no matter what happens. The ultimate goal is to flourish.”

6

Jun

During my visit in Chartres, I go to see the only African food store in town, “Exo La Difference”. As I walk in the door, a wave of heat surrounds me. The small fan in a corner is not doing much.

“Charly, it’s hot in here.” a customer says.

“It’s the heat of Africa,” Store owner Charly Musoso replies as if to say that is good for your health.

Sure enough, after a few minutes of sipping cold ginger beer from Jamaica, we all get used to the heat and enjoy the African ambiance. It is Friday afternoon and customers are streaming in.

When people come Chez Charly Musoso, they come for the atmosphere. Tall and heavy set, Charly lifts up cans of beers and restocks the refrigerator all while chatting cheerfully with customers of different nationalities: Congolese, Senegalese, Moroccan, Malian, Indian and so forth. Various African languages can be heard.

“This kwanga, how much?” A customer asks in Lingala, a national language of Congo.

“”2.80 Euros as usual,” Charly replies in the same language.

The only way you know you’re still in France is because the French Open is showing on the television set and the Spanish tennis star Rafael Nadal is playing an hour away from Chartres in Paris.

“For me, this is not just a store,” says Charly, who opened his business more than 10 years ago. “It’s really a cultural center.”

He greets a customer from Madagascar, with whom he often discusses the politics of his client’s country. Charly’s name is on everyone’s lips. It is as if people who walk in are here to visit a friend. The warm hospitality in Charly’s store is what brings the clientele back again and again.

“It’s the way you feel welcome here,” A young woman from Cote d’Ivoire said. “You feel you are here with a brother.”

Charly is helping a customer find a fish. He opens one of the four freezers placed in the middle of the store and digs through freshly frozen fish and salty ones. The other freezers are full of chicken and African and Caribbean vegetables.

The exotic merchandise chez Charly is the other attraction. Kwanga wrapped in banana leaves _ a sort of tough dough made out of cassava flour _ can be found in cartons next to walls of palm oil and sardines. Close by are piles of powder milk cans that remind me of home. It was my favorite drink when I was a little girl. I almost buy one on impulse.

More customers arrive, coming to shop for rice, fish, and yam and also chat with friends before heading home for supper. I reluctantly leave this African hub, but there is more to see in Chartres.

I spent the weekend with my friend Cyprian Josson, a radio journalist I met 11 years ago in Chicago.

Chartres is his turf; he is the founder of Le Festival International du Gospel de Chartres.

As we visited the ancient medieval town, we stopped by the famous Cathedrale de Chartres, dropped our backpacks on its steps and filmed a short video to promote his festival.

2

Jun

When I ride the métro in Paris, I flip through the readily-available free magazines, “A Nous” and “Métro.”

I sometimes find weird news that send me rolling with laughter. Then I make postcards out of them.

Such is the case with “Cherche fiancee vertueuse,” which literally means “looking for a virtuous fiancee.” It’s a dating service for Eastern European Orthodox would-be priests.

Here are the instructions…

“Open an account, introduce yourself with pious details, click on the button “Lord Jesus Christ, son of god, have pity on us!” then wait to be courted by the servants of the lord.”

Before getting ordained, Orthodox theology students have to be married. If not, they become monks.

Hence, the rush.

Enjoy the homemade postcards and have a great weekend!

Kabuika

http://kabuikakamunga.com

Above is a postcard I made out of an ad found in one of those free daily papers one can pick up at any metro station in Paris. The central ad reads,

“Thierry, married man. Elegant executive with humor, fit to be seen, wishes to engage in extra-marital relationship in all discretion and security with woman in similar situation.”

The ad ends with a phone number, not a cell phone number, but a landline telephone number!

That’s kind of shocking since the ad is placed in a Western society where monogamy is the rule.

I recently asked the patriarch of my family why so many Baluba men have multiple wives. He replied, it is so they would not go looking for other women elsewhere.

His answer surprised me since I had expected Luba polygamy to exist for the purpose of engendering as many children as possible. Children are the primary reason for polygamy, my uncle admitted. A reader had guessed well, regarding the story “Multiple Wives.”

Luba men are polygamous in order to have a lot of kids, who will later care for them as they grow old. So yes, it is a form of social security system.

However, the Luba society allows men to marry several wives for a second very good reason.

“Men are going to run after many different women anyway,” my uncle said.

Personally, I don’t believe that all men (Luba or not) are all womanizers. My uncle himself has only had one woman for 60 years.

The patriarch carried on. Luba men are encouraged to make those relationships legal and public, One. So that there could be no illegitimate children. Two. So that those men would be fully involved in the lives of their several wives. This was a good way to keep them busy and decrease the likelihood of them wandering in the street looking for more.

So here is an idea.

If French men start to marry let’s say two or three women, they would be so occupied with their wives that they won’t have time for any extra-marital affairs.

You see, the Luba resolution could potentially be used to solve the French quandary.

1

Jun

I know I am in France, because everywhere I look I see beauty.

This was my first impression when I took my first walk in the town of Saintry sur Seine. It still is.

A 60-year-old-looking Frenchman is sweeping his wooden gate as I walk by.

“It has to be clean.” He tells me with a shrug and a smile.

I smile back. The Frenchman seems to have come out of a postcard. All he needs is a beret.

Everything in France is old and charming. You can feel the centuries of stories in every nook and stone. I admire the old wooden door with its rough iron handle.

Gates here could be the subject of an entire photography book. They are all so different and original.

French people have a particular eye for beauty. In early April, the purple-scented flowers showered me with their perfume as I walk underneath them on the sidewalks. The following month, the town is now decorated with potted flowers at every window, framed with wooden shutters.

For me France is a guide post in this stage of my new life, pointing in the direction I choose to take. And because these sign posts are French, they do so with charming details, on a backdrop of the river Seine.

31

May

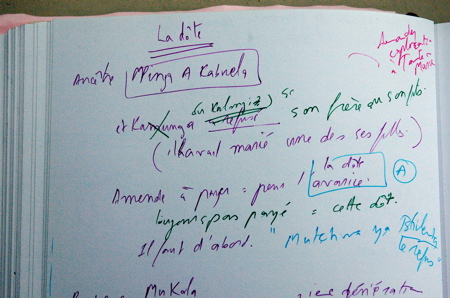

Five hours! Five hours I spent with my uncle Tshimanga, learning about one thing and one thing only: the dowry.

“It’s the cement!” My uncle repeated. “The cement that binds all the members of the family together. With the dowry system, everyone in the family gets a chance to marry. And so the family continues to grow and is strengthened.”

The dowry _ “la dote” in French _ is the base of an informal barter system created within our family. This swapping strategy acknowledges that everyone in the family has the right to get married no matter what their economic status is.

My uncle used to have the family dowry book. He lost it in his move to France more than a decade ago. Fortunately, he knows all the dowries by heart: the ones given by our family and the ones received.

I imagine the family book was written like an accounting book, keeping track of all dowry transactions. The book must have been filled with the “who’s who” of all our family marriages.

Following all this was very important, you see, since the person who helps you marry is in fact the one who shells out the dowry money for you to be able to get married. It’s like giving out a bank loan.

Since the Luba society is patriarchal, it is the men who marry the women; so they are the ones who pay the dowry to the women’s families.

My father, for example, helped his younger brother (Uncle O) get married: He paid for his dowry. Thanks to my Dad, my uncle O was able to start his own family and have children. A few years ago, Uncle O’s oldest daughter got married (her husband paid a dowry for her). That dowry was used to reimburse my Dad.

I imagine, the family ledger of these dowry transactions to look like this:

DOWRY BOOK:

Papa —> pays —> : Uncle O. marries (in 1975)

: Dowry = 1,200 FC (Congolese francs) [Out flow of cash]

Uncle O’s daughter gets married (in 2000)

<— : Dowry received = $500 (US dollars) [In flow of cash]

Papa gets reimbursed receiving $500.

I don’t know what 1,200 FC would amount to, but remember the amount of each dowry does not matter. What counts is one dowry reimbursing the other.

My paternal grand-father was the mastermind behind this dowry system. He wanted to make sure that after he passed away, his older sons will be able to help his younger ones get married. The dowry organization he created goes in even greater details, planning for all possibilities.

Even if the older sons do not have enough money to help out, it’s the dowry of their second daughters that will be used to help their younger siblings get married. Once again, I am using my Dad as an example.

Papa’s second daughter (my sister) got married. He received her dowry, turned around and used it to help his younger brother (Uncle M.) get married.

And so in the far, far future when my niece, who is about 5 years old now, gets married, my Dad will get reimbursed. Her future dowry will pay back the dowry debt that helped her father get married and bring her to the world.

Dowry debts are never forgotten!

If a dowry is not reimbursed within the lifetime of a donor, his brothers _ representing him _ will get compensated. If none of his siblings are alive, then his descendants will get reimbursed.

There is such a dowry debt in my family that has lasted for 5 generations. It is finally about to be paid.

30

May

So you have fallen in love with a Luba woman and asked her to marry you. Contrary to Western norms, this is only the beginning of a long journey to marriage.

STEP #1: You need to introduce yourself officially to your girlfriend’s parents. Avoid going alone.

I still remember my sister’s boyfriend coming to introduce himself. He came to our house _ alone _ with my sister hanging on his arm, very much in love. The boyfriend was not wearing a suit, but was rather dressed as if he was going to a party: flashy shirt and pants, topped with pink glasses shaped as hearts. I knew right away this was not going to be a good introduction. I was right. My Dad arrived, took one look at the scene, barked “What is going on here?” and threw the young man out of the house.

To show up alone at our house signaled to my Dad that this man was not taking himself seriously, nor respecting our family. For Luba people, marriage is a serious matter; it is a contract not only between two individuals, but also between their two families. So a suitor must come with his parents and siblings to ask for the girl’s hand. My sister’s boyfriend had to re-introduce himself properly _ this time with his family members.

THE UNOFFICIAL STEP #2: Expect to get investigated.

The Luba investigation has to do with integrity. Both families will likely do a background check on each other to see if the man (or the woman) is indeed what he portrays himself to be and that there are no skeletons in his closet.

Paranoid, you think?

My family started to ask around about my sister’s boyfriend: his job, his habits, who was his family? Where did they all go to school … everything. It turned out the man was separated, but still legally married to his wife AND he had children; details he had failed to mention to my sister. Thanks to this investigation, my sister had all the facts laid out in front of her and was now free to make a decision with more clarity.

STEP #3: The Dowry.

You have survived the investigation and are still considered marriage quality. Congratulations! Now we can proceed.

It doesn’t matter whether you are American or French, whether this is the 21st century or the 19th. When it comes to marrying a Luba woman, you can only do so the Luba way _ with a dowry.

The dowry has several objectives, but for the sake of this article, we will focus on one meaning. “La dote,” as it is called in French, is a marriage contract, the symbol of agreement between two families.

The dowry can range from 50 cents to more than 1000 euros. Before modern money, the dowry was paid in Luba currency of copper crosses. The girl’s family determines the amount, which in itself is not important. It is the token of the dowry, changing hands from one family to the other, that is crucial.

If you accomplish all these steps, you will be well on your way to winning the hearts of your future Luba in-laws.

I have left out a few details, goats and such… but you’ll find out later.