31

May

Five hours! Five hours I spent with my uncle Tshimanga, learning about one thing and one thing only: the dowry.

“It’s the cement!” My uncle repeated. “The cement that binds all the members of the family together. With the dowry system, everyone in the family gets a chance to marry. And so the family continues to grow and is strengthened.”

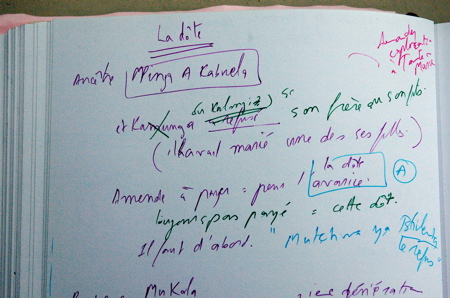

The dowry _ “la dote” in French _ is the base of an informal barter system created within our family. This swapping strategy acknowledges that everyone in the family has the right to get married no matter what their economic status is.

My uncle used to have the family dowry book. He lost it in his move to France more than a decade ago. Fortunately, he knows all the dowries by heart: the ones given by our family and the ones received.

I imagine the family book was written like an accounting book, keeping track of all dowry transactions. The book must have been filled with the “who’s who” of all our family marriages.

Following all this was very important, you see, since the person who helps you marry is in fact the one who shells out the dowry money for you to be able to get married. It’s like giving out a bank loan.

Since the Luba society is patriarchal, it is the men who marry the women; so they are the ones who pay the dowry to the women’s families.

My father, for example, helped his younger brother (Uncle O) get married: He paid for his dowry. Thanks to my Dad, my uncle O was able to start his own family and have children. A few years ago, Uncle O’s oldest daughter got married (her husband paid a dowry for her). That dowry was used to reimburse my Dad.

I imagine, the family ledger of these dowry transactions to look like this:

DOWRY BOOK:

Papa —> pays —> : Uncle O. marries (in 1975)

: Dowry = 1,200 FC (Congolese francs) [Out flow of cash]

Uncle O’s daughter gets married (in 2000)

<— : Dowry received = $500 (US dollars) [In flow of cash]

Papa gets reimbursed receiving $500.

I don’t know what 1,200 FC would amount to, but remember the amount of each dowry does not matter. What counts is one dowry reimbursing the other.

My paternal grand-father was the mastermind behind this dowry system. He wanted to make sure that after he passed away, his older sons will be able to help his younger ones get married. The dowry organization he created goes in even greater details, planning for all possibilities.

Even if the older sons do not have enough money to help out, it’s the dowry of their second daughters that will be used to help their younger siblings get married. Once again, I am using my Dad as an example.

Papa’s second daughter (my sister) got married. He received her dowry, turned around and used it to help his younger brother (Uncle M.) get married.

And so in the far, far future when my niece, who is about 5 years old now, gets married, my Dad will get reimbursed. Her future dowry will pay back the dowry debt that helped her father get married and bring her to the world.

Dowry debts are never forgotten!

If a dowry is not reimbursed within the lifetime of a donor, his brothers _ representing him _ will get compensated. If none of his siblings are alive, then his descendants will get reimbursed.

There is such a dowry debt in my family that has lasted for 5 generations. It is finally about to be paid.

30

May

So you have fallen in love with a Luba woman and asked her to marry you. Contrary to Western norms, this is only the beginning of a long journey to marriage.

STEP #1: You need to introduce yourself officially to your girlfriend’s parents. Avoid going alone.

I still remember my sister’s boyfriend coming to introduce himself. He came to our house _ alone _ with my sister hanging on his arm, very much in love. The boyfriend was not wearing a suit, but was rather dressed as if he was going to a party: flashy shirt and pants, topped with pink glasses shaped as hearts. I knew right away this was not going to be a good introduction. I was right. My Dad arrived, took one look at the scene, barked “What is going on here?” and threw the young man out of the house.

To show up alone at our house signaled to my Dad that this man was not taking himself seriously, nor respecting our family. For Luba people, marriage is a serious matter; it is a contract not only between two individuals, but also between their two families. So a suitor must come with his parents and siblings to ask for the girl’s hand. My sister’s boyfriend had to re-introduce himself properly _ this time with his family members.

THE UNOFFICIAL STEP #2: Expect to get investigated.

The Luba investigation has to do with integrity. Both families will likely do a background check on each other to see if the man (or the woman) is indeed what he portrays himself to be and that there are no skeletons in his closet.

Paranoid, you think?

My family started to ask around about my sister’s boyfriend: his job, his habits, who was his family? Where did they all go to school … everything. It turned out the man was separated, but still legally married to his wife AND he had children; details he had failed to mention to my sister. Thanks to this investigation, my sister had all the facts laid out in front of her and was now free to make a decision with more clarity.

STEP #3: The Dowry.

You have survived the investigation and are still considered marriage quality. Congratulations! Now we can proceed.

It doesn’t matter whether you are American or French, whether this is the 21st century or the 19th. When it comes to marrying a Luba woman, you can only do so the Luba way _ with a dowry.

The dowry has several objectives, but for the sake of this article, we will focus on one meaning. “La dote,” as it is called in French, is a marriage contract, the symbol of agreement between two families.

The dowry can range from 50 cents to more than 1000 euros. Before modern money, the dowry was paid in Luba currency of copper crosses. The girl’s family determines the amount, which in itself is not important. It is the token of the dowry, changing hands from one family to the other, that is crucial.

If you accomplish all these steps, you will be well on your way to winning the hearts of your future Luba in-laws.

I have left out a few details, goats and such… but you’ll find out later.

29

May

It’s Sunday morning. I decide to watch the sunrise. The town I live in, Saintry sur Seine, is exactly what its name says, “Saintry on the river Seine.” The river Seine snakes through Paris and its banlieues. Being on La Seine means being in the valley. On either side of the river, hills ascend in the east and in the west. It will take some time for the sun to rise from above the hill and shine its rays on the small town. Perfect! That means an extra hour in bed for me before going out to shoot the sunrise.

After an early breakfast of baguette and hot chocolate, I’m on the road. The city is still asleep as I walk along La Seine. There are no cars, no early-bird construction workers, only the occasional homeless men asking for a cigarette. It feels like the sun is putting on a show for only me and the swan.

The swan glide silently on La Seine letting me take their portraits. I continue walking, my sandals crunching the black gravel. My steps harmonize like music as they combine with the ”Cock-a-doodle-doooo” of a nearby chicken, except that French chickens say “cocorico.”

Soon the motor sound of a barge breaks the tranquil morning. A blue barge, complete with a car on top, churns down the river.

I wonder what it is like to live on a barge? It is a common way of life in France. A barge (called peniche in French) sometimes carries a car for its owner to zoom to work every morning, I imagine. Barges here even have mailboxes on the river banks for the mailman to bring letters and packages to the river people.

I walk for about an hour and reach the next city called Corbeil.

In Corbeil, my sunrise walk ends with a view of la Mairie (city hall) and a bird flying over the city, waking up.

This weekend I will be resting for Shabbat as usual. Afterward I will interview my Aunt Malu (seen in the picture above).

There is one minor detail to this plan: my aunt doesn’t speak French. And I barely know any Tshiluba.

No worries, I tell myself, this issue will only spice up our conversation.

I look up some synonyms of ’spice up’ on Thesaurus.com:

“animate, brace up, brighten, divert, entertain, excite, fire up, galvanize, give life to, invigorate, jazz up, juice up, quicken, spark, stimulate, vivificate, vivify, wake up, zap.”

Yep! I can visualize the interview already.

Thank you for reading my stories. Your comments and emails are very much appreciated. Feel free to contact me on my website by filling out the contact form: http://kabuikakamunga.com.

See you next week with new stories of my travels, including “If you want to die quickly, sleep with a Luba woman.”

When it comes to methodology, genealogists say there are three ways of gathering information: find documents in family homes, interview parents, and visit cemeteries.

Now let’s look at this from a Congolese perspective.

Method #1. Find documents such as birth certificates.

That’s only possible when the family is living in the West. If you ask someone in the Congo to send you a copy of a birth certificate, you could wait a while, a long while.

I have a cousin in Europe, who requested a copy of his birth certificate from Kinshasa. He had to wait 6 months to receive it. And when the document arrived, the place of birth was wrong. It said he was born in Kinshasa, instead of Lubumbashi. Not wanting any further delays, he did not request another one. So now in his immigration status in Europe, he officially was born in Kinshasa.

This would be alright … if he didn’t have a twin sister.

Place of birth of my cousin: Kinshasa

Place of birth of my cousin’s twin sister: Lubumbashi

Welcome to my genealogy world!

Method #2. Interview parents, grand-parents, uncles, aunts, and anyone you can get hold of.

This we can do! That’s about the only sure thing we can do in African genealogy since we have a strong oral history culture. In our large families, elders are the guardians of collective memories and are eager to pass on the knowledge to the next generations.

In Paris, I am immersed in oral history. Knowledge is given though stories colored with humor, laughter and the storyteller’s personal snazziness. Read any of my earlier blog entries and you’ll get a taste of it.

Method #3. Visit family tombstones to find names and dates of birth and death.

That works only in well-kept cemeteries like in the West (or even in Morocco). When you die in Kinshasa, you have a chance to be “found” if you get buried in an expensive cemetery, maybe alongside diamond businessmen and powerful politicians. I remember my mother trying to find her father’s tomb a few months only after he passed away. She came back from the cemetery laughing. She never could find it. Overgrown vegetation had taken over the graves.

So do you think that the next time I am in Kinshasa I will find my grand-father’s tomb? Not a chance!

Sitting with my uncle on a Sunday afternoon, I ask him how he got married. My aunt and him had recently celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary. His face lits up and he says:

“We got married on a Wednesday.”

O.k.! So back in the days, people got married on Wednesdays and today many Christian weddings occur on Saturdays. No big deal.

No, my uncle explains, Saturday weddings were called “Les mariages a Njiji,” the weddings of flies, of insects. People who got married on Saturdays were not virgins. These were people who lived together and even had children already.

So if you were virgin (especially the woman), you got married with dignity on Wednesday and the bride got to wear a white veil. We are talking about a religious wedding here; so even in the 1950s, religious weddings in the Congo looked very much like any weddings in the West.

While a white veil and a Wednesday wedding were the Christian rewards for virginity, among the Baluba (particularly the Bakwa Dishi people), you get a goat. Not just any goat! It’s the “Mbuji Wa Nyima,” the goat that is given after the wedding.

Here is how it works. Soon after the consummation of marriage (which determines with certainty that the woman was indeed virgin), the husband has to bring a goat to the woman’s family to thank them for having raised their daughter well.

Now, you see, my Mom was both a Christian and a Mukwa Dishi. She had her Wednesday wedding with a white veil in a Catholic church in Liege, Belgium where my Dad was studying medicine. Since they were in Europe, my Dad decided they would wait until they returned to the Congo to bring a goat to her family.

Years passed by and two children later, my Dad kind of forgot about that obligation, until my Mom suddenly shouted,

“And where is my goat?”

My Dad with all his medical degrees and high social status, had to go back to my Mom’s village and present the goat to her family as a thank you.

25

May

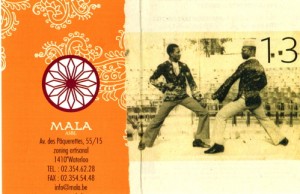

I rarely buy postcards. I create them instead.

During my travels, I enjoy reading local newspapers, magazines, pamphlets … anything printed, really. This way I get to discover interesting aspects of the culture I am in.

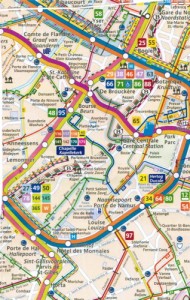

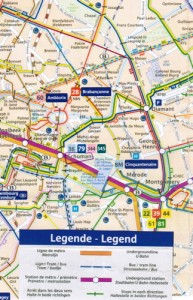

Then I make collages of the most appealing bits. The postcards are snippets of my travel memories: a map of the métro in Bruxelles, a local exhibit going on in the city or just something that attracted my attention.

In Bruxelles, I went to a cool store called Mala India, took the métro everywhere, enjoyed listening to the Flemish language, and wished I had time to hop over to Antwerp and go see Seydou Keita Photography.

So here are my homemade postcards.

If I thought my family was the only unusual one on the planet, I was wrong. Other family stories beat us hands down in African genealogy adventures.

My friend Myriam, who is Parisian of Moroccan origin, told me that in order for her mother to know her own birthday, she had to go to a cemetery in Morocco.

The tradition there was to tell people: “You were born 2 days after this person passed away. Or 7 days before so and so died.” So to know your birthdate required visiting tombstones to substract or add days to another person’s death date.

In this rare case, to be Congolese is easier. All I have to do is go to the patriarch of my family and get all the birthdays.

“What is grand-father’s date of birth?”

“I don’t know. He was pagan.”

Well, almost all the birth dates. The ones that are missing are those of my ancestors who were pagans.

Dates were not important in our Luba traditions, only events and the order of births. Later on, Catholic missionaries began to keep track of birth records.

So if you were Christian, you knew your birthday.

23

May

Bruxelles _ My niece Ngoya is coming to pick me up. I had not seen her in 5 years. She lives in Kinshasa and we are both in Belgium at the same time for a few days. When she arrives, we sit down over ice cream and chat. A Belgian friend of mine joins us.

He must have been smitten by my niece, because right away he starts to talk about how beautiful she is. Soon the word marriage pops out of his mouth. I look at him in shock. My niece pretty much ignores him, as she texts on her Blackberry.

Luba Dating: Taboo #1.

Don’t talk about marriage the very first second you meet a girl. And even if you are kidding, you do not joke about such things. His behavior was inappropriate, especially among the Baluba.

The following day, since my Belgian friend is a nice guy, I decide to tell him gently the faux pas he had committed.

“Dude! You were hitting on a girl in front of her mother. You don’t do that.”

As he looks at me puzzled, I continue. For Luba people, there is no concept of niece or aunt. These words do not even exist in the Tshiluba language. My niece is actually my daughter and I am her mother.

“In conclusion, you were wooing my daughter right in front of my eyes! AND without my permission!”

“Oh, so it would have been o.k. if you, the mother, had given me permission to date your daughter?” He asks.

“Even with my permission, you can’t slobber over a girl in front of her mother. It’s so vulgar. Besides, that will only make the girl run away from you.” No Luba woman would want a man who behaves like that.

(…unless of course, the woman was after his citizenship. But here, my Belgian friend is out of luck; my daughter-niece already has her Belgian citizenship. So no interest there).

“O.k.” my friend says “I’ll marry her and make it all proper.” He turns to a man who walks in the reception area and introduces me as his my mother-in-law.

Luba Dating: Taboo #2. You do not have permission (nor the honor) of calling anyone, your mother-in-law when you haven’t even paid the dowry.

Bye!

Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu wa Za Banga, President of Zaire

Here is a real dialogue (for the sake of privacy, names have been changed).

“What’s your husband’s name?” I ask my cousin A.

“Mobutu” she replies.

“Mobutu? I thought his name was Mutombo,” exclaims my cousin’s sister who has been sitting with us.

“Well, his real name is Mutombo, but his name in Germany is Mobutu.” Cousin A explains.

Confused? You’re not the only one. Here is what I think I understand.

Many Africans are determined to go abroad to the West in search of a better life _ by any means necessary; this includes traveling with someone else’s passport sometimes. I don’t know exactly what is my Cousin A’s husband’s immigration status, but I’m thinking new name, new country, new life.

Now try to keep track of all that in genealogy! They don’t even have such categories in genealogy softwares.