If you want to die quickly, sleep with a Luba woman.

Wait a minute! I know what you’re thinking.

You must be saying, “a few weeks ago you wrote about how to marry a Luba woman (see story); now you’re telling us you can die if you sleep with her?”

Not exactly. If you have given a dowry for her, you are safe. If you have not, that’s when you die. Death is issued as a punishment for breaking the Luba law: sleeping with a woman you have no business sleeping with.

You might feel this is a bit harsh. However, one must understand the ramifications of such an act. In the traditional Luba society, when a woman sleeps with a man and that fellow does not marry her, she loses the chance of ever getting married. No marriage means no dowry received. Her whole family might crumble (see Book of Dowry).

So you can see why the woman’s family would want to kill you. You get the choice of two types of death, depending on the family you have offended.

Some have a tendency to kill by poison. In my village, I think it would be by lightning. We think it’s more precise. The outraged family would wait until you are alone in the house, then will send lightning that will burn down the house with you in it.

At the National Library of France yesterday, I found a kasala, a Luba song that tells the story of a man who slept with a woman and was punished by lightning. The man was named Kayembe and the song was written from his perspective. My guess is Kayembe did not survive the lightning strike and the song was post-mortem:

Kayembe A.K.A. “The-Vagina.”

My brothers and sisters, tell me:

What did I do that was so serious?

I did not stab G-d

I did not even insult Him.

All I did was admire beauty!

31

May

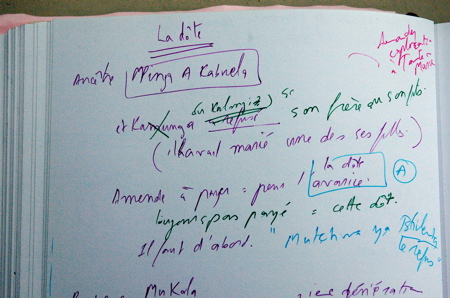

Five hours! Five hours I spent with my uncle Tshimanga, learning about one thing and one thing only: the dowry.

“It’s the cement!” My uncle repeated. “The cement that binds all the members of the family together. With the dowry system, everyone in the family gets a chance to marry. And so the family continues to grow and is strengthened.”

The dowry _ “la dote” in French _ is the base of an informal barter system created within our family. This swapping strategy acknowledges that everyone in the family has the right to get married no matter what their economic status is.

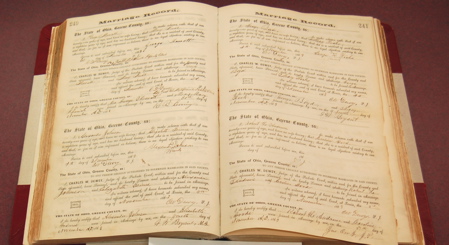

My uncle used to have the family dowry book. He lost it in his move to France more than a decade ago. Fortunately, he knows all the dowries by heart: the ones given by our family and the ones received.

I imagine the family book was written like an accounting book, keeping track of all dowry transactions. The book must have been filled with the “who’s who” of all our family marriages.

Following all this was very important, you see, since the person who helps you marry is in fact the one who shells out the dowry money for you to be able to get married. It’s like giving out a bank loan.

Since the Luba society is patriarchal, it is the men who marry the women; so they are the ones who pay the dowry to the women’s families.

My father, for example, helped his younger brother (Uncle O) get married: He paid for his dowry. Thanks to my Dad, my uncle O was able to start his own family and have children. A few years ago, Uncle O’s oldest daughter got married (her husband paid a dowry for her). That dowry was used to reimburse my Dad.

I imagine, the family ledger of these dowry transactions to look like this:

DOWRY BOOK:

Papa —> pays —> : Uncle O. marries (in 1975)

: Dowry = 1,200 FC (Congolese francs) [Out flow of cash]

Uncle O’s daughter gets married (in 2000)

<— : Dowry received = $500 (US dollars) [In flow of cash]

Papa gets reimbursed receiving $500.

I don’t know what 1,200 FC would amount to, but remember the amount of each dowry does not matter. What counts is one dowry reimbursing the other.

My paternal grand-father was the mastermind behind this dowry system. He wanted to make sure that after he passed away, his older sons will be able to help his younger ones get married. The dowry organization he created goes in even greater details, planning for all possibilities.

Even if the older sons do not have enough money to help out, it’s the dowry of their second daughters that will be used to help their younger siblings get married. Once again, I am using my Dad as an example.

Papa’s second daughter (my sister) got married. He received her dowry, turned around and used it to help his younger brother (Uncle M.) get married.

And so in the far, far future when my niece, who is about 5 years old now, gets married, my Dad will get reimbursed. Her future dowry will pay back the dowry debt that helped her father get married and bring her to the world.

Dowry debts are never forgotten!

If a dowry is not reimbursed within the lifetime of a donor, his brothers _ representing him _ will get compensated. If none of his siblings are alive, then his descendants will get reimbursed.

There is such a dowry debt in my family that has lasted for 5 generations. It is finally about to be paid.

23

May

Bruxelles _ My niece Ngoya is coming to pick me up. I had not seen her in 5 years. She lives in Kinshasa and we are both in Belgium at the same time for a few days. When she arrives, we sit down over ice cream and chat. A Belgian friend of mine joins us.

He must have been smitten by my niece, because right away he starts to talk about how beautiful she is. Soon the word marriage pops out of his mouth. I look at him in shock. My niece pretty much ignores him, as she texts on her Blackberry.

Luba Dating: Taboo #1.

Don’t talk about marriage the very first second you meet a girl. And even if you are kidding, you do not joke about such things. His behavior was inappropriate, especially among the Baluba.

The following day, since my Belgian friend is a nice guy, I decide to tell him gently the faux pas he had committed.

“Dude! You were hitting on a girl in front of her mother. You don’t do that.”

As he looks at me puzzled, I continue. For Luba people, there is no concept of niece or aunt. These words do not even exist in the Tshiluba language. My niece is actually my daughter and I am her mother.

“In conclusion, you were wooing my daughter right in front of my eyes! AND without my permission!”

“Oh, so it would have been o.k. if you, the mother, had given me permission to date your daughter?” He asks.

“Even with my permission, you can’t slobber over a girl in front of her mother. It’s so vulgar. Besides, that will only make the girl run away from you.” No Luba woman would want a man who behaves like that.

(…unless of course, the woman was after his citizenship. But here, my Belgian friend is out of luck; my daughter-niece already has her Belgian citizenship. So no interest there).

“O.k.” my friend says “I’ll marry her and make it all proper.” He turns to a man who walks in the reception area and introduces me as his my mother-in-law.

Luba Dating: Taboo #2. You do not have permission (nor the honor) of calling anyone, your mother-in-law when you haven’t even paid the dowry.

Bye!