5

Jul

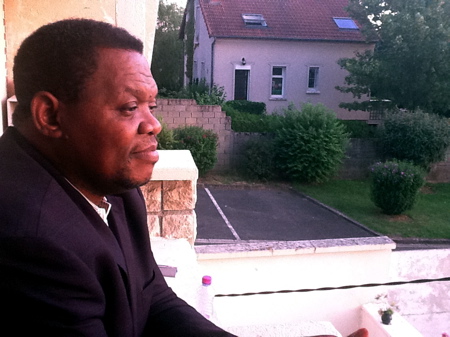

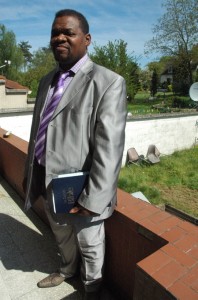

My cousin Kabeya is a pastor in France.

He comes home one day, walks heavily up the stairs and states, “the life of a pastor is something else, I can tell you that.”

It is a life of schedule, he tells me, a very tight schedule. There is the Sunday service for which he needs to prepare a sermon. Wednesday is the prayer meeting and Friday, the bible study group. The choir rehearses in all the rest of the weekdays. And Saturday, the last free day, is filled with youth meetings and the Christian library hours.

And that’s without counting the emergencies, deaths, weddings and accidents, which constitute my cousin’s pastoral service.

“I have been called at 3 a.m.,” he tells me.

It was a couple, who had been quarreling. They said: “You prayed for our marriage, now come and pray for our divorce.”

So my cousin the pastor got up from bed and went to the couple’s house, not to pray for their divorce, but rather to reconcile them.

Even when my cousin is simply a guest at a wedding, he ends up working.

He recounts the time when sitting in the church pew, the pastor, overwhelmed, suddenly left. There was so much arguing between the two families that the girl’s family did not want the wedding anymore. When they decided to go ahead with the wedding, they called my cousin from the pew to officiate the wedding.

Kabeya has married many people. The band at the wedding gets paid. The newlyweds get gifts. And he gets nothing. He often works without any renumeration.

“You work without getting paid,” He confesses. “And tomorrow, if these same people insult you, you can’t chase them away. You must continue to love them.”

Kabeya has lived for years with such daily obligations and responsabilities. His life is based upon the church.

“You come home with your church, talking and thinking about it nonstop,” he says. ”With such a schedule, you don’t see your children grow.”

His oldest son recently got married.

During my stay in France, I have watched Kabeya pour his energy into every person who seeks his counsel.

Although my cousin is now a bishop (which I understand it to be a sort of supervisor for pastors), he continues to work hard.

I have heard him on the phone in the middle of the night teaching, encouraging people, and praying with them. I have heard him at 1 a.m. and even at 3 a.m. Then he gets up at 4:30 a.m. for his morning prayers.

I often wonder if my cousin ever sleeps.

To recharge his energy, he reads inspirational books, listens to preachers on television and in his car radio, and goes to conferences to keep updated.

Kabeya’s church is called Centre du Plein Evangile, his ministry is Centre de Réussite. He wants to create a financial cooperative that will be a formidable tool for everyone. He often travels between France and Canada to preach and build his ministry.

Kuteki-teki;

Kuena umanya muamba tshidimu;

Maweja m-muena kukosolola. (Tshiluba)

Ne soyez pas un entasseur de biens;

Vous ne savez pas ce qui se passera pendant l’année;

C’est D’ieu qui mesure le temps de votre vie. (French)

Don’t accumulate material possessions;

You do not know what will happen during the year;

It is G-d who mesures the length of your life. (English)

The Meaning:

Tomorrow is a day G-d only knows about. You could accumulate things as much as you want and still die unexpectedly. Papa Tshimanga gives the example of a man who planned and accumulated possessions for years to come. He died in his sleep one night and never got to use his wealth.

The exodus began on June 24th when public schools in France closed for the summer vacations. Immediately, parents packed their children and boats to head out for the sea or to Spain.

“Would you like to sign up for the children movie and picnic?” The librarian asks a parent.

“No, we won’t be there.” she replies.

As I browse through books at the local public library, I hear the same scenario over and over again with the librarian asking and the parents announcing they’re going out of town.

Maybe it’s just French parents who are leaving Paris.

I take the train to Paris today. It’s a sunny day. I want to hang out by La Seine. There are a few artistic péniches there; maybe I will find some artists and interview them.

In front of la Péniche Anako, the poster of events shows a busy month of daily concerts. Anako is a floating cultural center, complete with an auditorium. I ask the barman about meeting some artists.

“They’re all leaving,” he said. “We’re leaving too.”

Their last concert is on Sunday and they’re leaving Tuesday.

“Try la Péniche Antipode, two boats down,” he adds. “Maybe they’ll be staying for the summer.”

At the designated barge, musicians are busy loading up la Péniche Antipode with musical instruments and sound system to gear up for tonight’s pop concert. Music is already blasting through the speakers. On the deck, I hold on to the railing as the barge waves because a tourist shuttle boat speeds by.

I approach the young man smoking near the bar; he has short blond hair, except for one dread lock dangling on the back of his head. He explains that they will be travelling on their boat, staying one month in a banlieue of Paris up north, then the next month, at another town. So no, they won’t be in Paris this summer.

I leave thinking that next time I want to do a story series on Paris, I will have to do it during the year when all Parisians are in town.

They say in the Summer, Paris is left to tourists.